US Bank Stress Test to be Released-Pay Back Time

Goldman Sachs and other banks want to pay back bail-out cash. But the banking system is not in the clear yet

Using taxpayers’ funds to prop up America’s banking system was a necessary evil. So in many ways it is welcome that some banks now want to repay the money. On April 14th, six months after getting $10 billion from the Treasury, Goldman Sachs sold $5 billion of new shares with that in mind.It is easy to see why. Some banks, including Goldman, say that back in October they had enough capital and took part in the bail-out only to show solidarity with the government’s plan. Since then they have been excoriated by Congress and now face restrictions, mainly on pay but also on hiring foreigners, that Lloyd Blankfein, Goldman’s boss, says “limit our ability to compete”. Meanwhile banks’ shares have soared on optimism about their profits. Goldman says that repayment is a “duty”. But who wants to rely on livid voters and banker-bashing politicians when private cash is available?

The principles for letting a bank repay bail-out cash are clear. Its capital position must remain strong: capable of at least maintaining its lending book, absorbing shocks, and commanding enough confidence to allow borrowing without state guarantees. It should repay taxpayers by selling new shares or retaining profits. For a bank to boost capital by withdrawing credit or exiting important business lines would be counterproductive. It must have healthy profits and sane risk and pay policies. European banks, such as HSBC, that have got there without state support have rightly been applauded.Does Goldman pass these tests too? Although it has just reported bumper earnings (see article), their quality was mixed, and relied too much on volatile trading. It has a slug of hard-to-value assets and its borrowing costs have yet to return to normal; it is still using the government’s debt-guarantee scheme. But its regulatory capital ratios are solid, half as strong again as those of America’s ten biggest banks overall. When the Treasury completes its stress tests to evaluate the largest banks soon, Goldman should pass with flying colours.

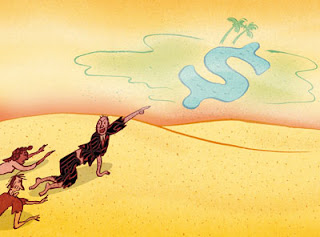

No bank is an island

Yet the crisis has shown that banks do not exist in isolation. Some say that by letting lenders repay the state, those unable to do so would face runs on their shares and junior debt. This cannot be made the sole consideration—the banking system should not walk at the pace of its weakest members. However there is still a danger that the American banking system as a whole is nearly insolvent. And if the stress tests are rigorous, they could show that insolvency is indeed some banks’ likely fate: losses may well eat up much of the system’s capital.

The slim margin for error means confidence could still evaporate, with even good banks dragged down by counterparty risk. The government says banks that fail the stress tests must raise capital within six months (from the state if necessary) and sell toxic assets. The tests must not be fudged. Providing that the six-month deadline is a firm one, forcing Goldman and others to retain their unwanted funds till then seems fair. But that is long enough. Meanwhile, the politicians should stop changing the rules about pay and bonuses.

* U.S. to reveal test guide April 24, results May 4

* Officials trying to prove legitimacy of test, results

* Questions linger about TARP funding, fate of weak banks

* Tests may show need for at least $100 billion capitalU.S. regulators on Thursday released some details about their bank "stress tests," moving to bolster the credibility of a process some investors worry might not reveal the financial sector's true health.

An official at the Federal Reserve said on Thursday that results of the tests, designed to see how the nation's 19 largest banks would fare should the U.S. recession prove unexpectedly severe, would be made public on May 4.

Regulators will try to prove the rigor of the tests by releasing a document on April 24 that will explain the underlying assumptions, the official said. The document will outline the methodologies employed and serve as a guide on how to interpret the results.

The test results will include a capital recovery plan for banks that regulators determine would be short of capital if the economy's downturn gathered steam and unemployment shot unexpectedly higher.

Experts say the results must be believable and the recovery plans clear, or officials risk further destabilizing the financial system in a way that will send the weaker banks into a downward spiral.

"There is a lot at stake," said Douglas Elliott, a former JPMorgan investment banker now with the Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank. "It's going to be important that this is viewed as a test that really has validity."

Regulators have not made final decisions on how to present the results, the Fed official said. Regulators will disclose at least some of the information, but no decision has been made on whether banks themselves will disclose some as well.

The official, who requested anonymity because the tests are still in process, added that the goal is to ensure that all the results are presented on a comparable basis.

The results are expected to distinguish which banks are strong and on the path to recovery, and which firms remain in need of government aid -- and subject to caps on executive pay and other restrictions. Stronger banks are likely to fare much better at attracting private capital and removing any stigma associated with taxpayer funds.

Some banks have already declared themselves among the strong.

JPMorgan Chase Chief Executive Jamie Dimon said on Thursday "we think we'll do fine under any stress tests measurement," adding that the bank could immediately repay the $25 billion it received from the government.U.S. regulators on Thursday released some details about their bank "stress tests," moving to bolster the credibility of a process some investors worry might not reveal the financial sector's true health.Goldman Sachs similarly trumpeted its health on Tuesday, saying it has a "duty" to repay $10 billion in taxpayer aid. It sold $5 billion in stock toward that effort.

Wells Fargo surprised the markets last week, saying it expected to post a $3 billion first-quarter profit.

TESTING STRESS, LEGITIMACY

Regulators plan to hold discussions with the banks about the standardized stress tests from April 24 through May 4, according to the official.

Once the test results are announced, banks found to need more funds will have six months to raise the capital from the private markets or can take an infusion of taxpayer money.

Announced in February, the tests are designed as an exercise to provide credible information on the health of the U.S. banking sector. Regulators hope that once investors have the results, they can accurately evaluate the health of banks' balance sheets, and private capital will return to the sector, stabilizing the financial system and increasing lending.

More than 200 examiners have spent weeks poring over the banks' portfolios and asset valuations.

James Wheeler, a partner on the financial institutions team at law firm Bryan Cave, said the stress tests have been much more extensive than routine stress tests conducted at banks. The current round involve extensive modeling of banks' loans and investments, include higher risk multiples, and project out further in the future, he said.

"It's not a new species but it certainly is the next generation," Wheeler said.

Treasury has laid out some details of the economic scenarios it used to stress test the banks, but the rigor of the test alone will not make the results believable, Brookings' Elliott said.

"Unless the test results show, the need for at least $100 billion of capital, a lot of people aren't going to think the results are credible," Elliott said. "I can't imagine officials wanting it to be $300 billion, and it's not clear they could get the money from Congress."

Treasury has said any new capital injections would come from the $700 billion financial rescue fund approved by Congress in October. Treasury officials estimate they have about $134.5 billion they could still tap.

Some analysts and financial industry insiders think regulators will go beyond current plans to simply recapitalize banks and take toxic assets off bank balance sheets. They see the possibility of management shake-ups, mergers and possibly even the unwinding of some large firms seen beyond repair.

A financial industry source, who spoke anonymously because of relationships with the top banks, said regulators will have to state clearly what will happen to the weaker banks with capital holes, or risk a severe market reaction.

"It's designed to inspire confidence, but creates a whole new set of expectations in the market that, if not met, can totally backfire," the source said.Still Others Say "There is no real stress Test going on"

William Black is a former senior bank regulator, best known for his thwarted but later vindicated efforts to prosecute S&L crisis fraudster Charles Keating. He is currently an Associate Professor of Economics and Law at the University of Missouri - Kansas City.More germane for the purpose of this post, Black held a variety of senior regulatory positions during the S&L crisis.He managed investigations with teams of examiners reporting to him, redesigned how exams were conducted, and trained examiners.

He has confirmed our suspicions about the bank stress tests announced by Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner: they simply cannot be adequate, given the number and experience of the staff, and perhaps as important, their relationship with the banks (see detailed comments below).

I also asked him about the fact that bank examiners examine banks and would not have much (any?) experience in the capital markets operations or sophisticated products that the big investment bank, now banks, participated in. Goldman and Morgan Stanley ought to be subject to these exams; Citi, JP Morgan, and Bank of America have large capital markets operations. These firms are where the biggest risks and exposures lie. Do the examiners what to look for in a even the low-risk operations, like repo desks, much the less derivatives and proprietary trading books? He agreed (as presented below) that it was a near certainty that this was beyond their skill level.

Now this begs the question: why has the Treasury Secretary set in motion an obviously bogus process? It suggests the result is pre-ordained.

One possibility is that even a very quick and dirty look at many of the big banks' books will reveal them to be in very bad shape. In fact, the inadequate staffing could be part of the private conversation: "You know we didn't send in enough bodies to do this right, and even using your numbers, which we can assume in some cases will be flattering, you look like a goner."

But all of Geithner's actions to date are inconsistent with him taking a tough stand. Having a lot of people party to a process that finds that some of the big banks are in trouble would be hard to keep secret (to my knowledge, none of these people have high level security clearances. Government employees and contractors in those cohorts do keep their mouths shut). So I think it is more likely that the banks will get scorecards that show them to be in various stages of peril, but none will be found to be terminal. (They can't be given a clean bill of health, that would call the whole rationale of the TARP and its various injections into question, and also would put Geithner at considerable risk if any bank declared OK fell over in less than 12 months).

But even the designation of "sick but not ready to be hospitalized" carries with it risk to the Administration. If the banks get sicker than anticipated, how can they explain it? They can't say, "oh, things got worse than we contemplated". The whole point of a stress test is to anticipate worst case scenarios. And it is pretty certain a fair number of the big banks will be on such large-scale life support by year end that it will be hard to make a case not to put them in receivership.

Whatever statement Geithner puts out about the results of the stress test is likely to come back to haunt him, as did Colin Powell's "there are WMD in Iraq" speech before the UN did. And Powell had a better reputation going into Iraq than Geithner has in prosecuting his war.

From William Black:

There are no real stress tests going on.

1) If you did a real stress test, as Geithner explained them, you wouldn't just have a $2 trillion hole -- you'd impose regulatory capital requirements of 50%. (FYI, the regulators have the power to set HIGHER individual capital requirements based on unusually large risks at a particular bank.)

Yes here. By implication, the results of anything approaching a true stress test, plus reasonable regulatory responses, would dictate radical action. We have not seen any corresponding groundwork laid for that sort of thing. Back to Black:

2) You can't conduct a meaningful stress test without reviewing (sampling) the underlying loan files and it seems likely that the purchasers of securitized instruments (not just mortgages) do not even have the loan file data. Moreover, loss ratios vary enormously depending on the issuer, so even a bank that originates (or has purchased a bank that originates) similar product cannot simply take its own loss rate and extrapolate it to the measure the risk on the value of securitized credit instruments.

3) The regulators are overwhelmed because of personnel cuts (particularly heavy among their best, most experienced examiners that had worked banks that had engaged in sophisticated frauds. Buyouts were common, because more experienced examiners appear more expensive. This isn't true when you consider effecitiveness and productivity, but management didn't care about that. Treat what I write after the colon as hearing from me at my most serious and thoughtful: it is vastly more difficult to examine a bank that is engaged in accounting control fraud. You can't rely on the bank's books and records. It doesn't simply take more, far more, FTEs -- it takes examiners with experience, care, courage, and investigative instincts and abilities. Very few folks earning $60K are willing to get in the face of the CEO and CFO making $25 million annually and tell them that they are running a fraudulent bank and they are liars. FYI, this is one of the reasons why having "resident examiners" never works. The examiners don't even get to marry the natives. They get to worship God's annoited. Effective examination is good for you, but it is very unpleasant, ala a doctor's finger up your rectum. It requires total independence.

So, the examination force doesn't have remotely the numbers or the relevant experience and mindset to examine the largest banks with the greatest problems.

Yves here. Black is not using the fraud word lightly. He believe that we have Enron-level accounting fraud happening, now, in the financial services industry. And we have asked repeatedly, why has there been no investigation of fraud at Lehman? There was a $100 billion plus hole in its balance sheet, meaning a substantial negative net worth, when its financial statements presented a completely different picture. Back to Black:

4) As Geithner describes the process, NO ONE can conduct reliable "stress testing." It inherently requires testing everything in every way any and all aspects of everything could conceivably interact. It also doesn't provide any meaningful output that can be operationalized (unless you want to force an enormous rise in minimum regulatory capital requirements, which he obviously doesn't want to do).

5) Examiners certainly can't A) do the stress testing that Geithner describes or B) evaluate the reliability of a large bank's proprietary stress test. If they were serious about constructing reliable stress tests, which they aren't, you'd require their analytics to be made public. You'd have the industry fund independent investigations by rocket scientists chosen by a committee selected by the regulators of the soundness of the analytics. You'd also have the industry fund competitions to rip them apart (a bit like we hire legit hackers to test security by trying to defeat it) and show where they produce absurd results. The geeks would have a field day (that would probably last a decade). There are probably zero examiners that have the modeling skills required to evaluate the most sophisticated stress test models. The concept that there are 100 examiners with these skills, suddenly freed up from all other duties, assigned to CONDUCT stress tests is a lie.

6) It is, however, possible to use even the less experienced examiners to conduct a far more useful examination of the quality and value of nonprime loans. My nightmare scenario which I fear is often true is that A) because the biggest originators of nonprime loans were mortgage bankers, B) because every large mortgage banker that specialized in nonprime loans went bankrups, C) because many of them went into Chapter 7 liquidations and even those that went into Chapter 11's had little incentive to hang on to files on mortgage loans they had sold to other entities -- the loan files on many nonprime loans may no longer exist. (My fervent prayer is that the loan servicers have tapes with copies of the underlying loan files, but I fear that this prayer will not be answered.) Under this nightmare scenario it will be extraordinarily hard to determine loan quality and losses and very hard to foreclose against borrowers that can afford attorneys (admittedly a minority) and that claim fraud in the inducement.

Yves again. Remember, aside from the discussion of the bank's risk models, he is still framing the stress test in terms of more or less traditional banking activities, that is, that most of the assets that need examining are loans. I asked for how he thought the examiners would fare with more complicated products, like CDOs, CDS, and derivatives. His comments:

Yes, few examiners understand more exotic products. In my experience, nobody understands all the products. I certainly don't, and if I did I'm sure my knowledge would be out of date within weeks.

The problem is compounded by the fact that understanding how the product is actually used (CDS is a good example) v. how its proponents picture it as being used is essential. Understanding its sensitivity to credit and interest rate risk is well beyond the ken. Understanding the liquidity risks and interaction effects is out of the question.

Examiners rarely know that financial risks are not normally distributed, but have far fatter tails. (Nor do they understand why this makes truncating the VAR a recipe for disaster.) Examiners rarely understand that any econometric analysis undertaken during the expansion phase of a bubble will invariably find the strongest positive correlation with the worst possible business practices (because those practices maximize accounting fraud).

We were, 15 years ago, able to get some strong capital markets people and give them advance training. We sent them out on exams, they impressed the industry -- and they were promptly hired away from us at substantial raises

Some countries have found ways around this problem, but they don't translate well to America. In Japan, the most prestigious jobs are in the top ministries, so they get and hang on to good people. In Singapore, Lee Kwan Yew felt he had to depart from the typical corrupt Asian government norm for Singapore to prosper. Top government bureaucrats are paid like top private sector professionals (think law firm partners). They are well enough paid (or have the prospects of being well enough paid) so as to have an incentive not to screw it up (tough internal audits also help).

Comments