US Republicans and Democrats

CONGRESS and President Barack Obama return to work in Washington on September 8th, after Labour Day. But a summer of golfing has done nothing to improve the nation’s political temper. Democrats and Republicans are in the throes of one of their periodic shouting matches about who is to blame for the gridlock on Capitol Hill and, more broadly, about the merits and flaws of bipartisanship. “Now more than ever,” yelled a representative recent headline on salon.com, an online magazine, “bipartisanship is for suckers.”

Stoking the liberal side of this debate is Congress’s failure to make progress on health-care reform. A cacophony of voices is urging Mr Obama to stop seeking compromise with the Republicans, which seems wasted effort, and use Democratic votes alone to ram his flagship domestic project through Congress. It is not just the netroots who are up in arms: on August 30th an editorial in the New York Times concluded “with considerable regret” that the ideological split between the parties was too wide to bridge.

The White House is signalling impatience too. Mr Obama’s press spokesman, Robert Gibbs, complained this week that Mike Enzi of Wyoming, one of the three Republicans on the Senate Finance Committee who are supposed to be hammering out a compromise on health with three Democrats in Senator Max Baucus’s “gang of six”, had “turned over his cards on bipartisanship” and walked away. Mr Gibbs was responding to a radio broadcast in which Mr Enzi had excoriated the Democrats’ reform plans. If Mr Gibbs is right, the outlook for bipartisan reform has indeed darkened. The “gang of six” had seemed the likeliest forum to produce a bill that might attract cross-party support in the Senate.

For the moment, however, Mr Obama gives no hint of abandoning his (stated) preference for bipartisan lawmaking on health, climate change and other matters. This dispirits those Democrats who yearned, after eight years of George Bush, for audacious change. These loyalists are dismayed by Mr Obama’s recent softening of his insistence that any health reform must include a “public option” (under which private insurers would face competition from a government-run scheme). But Mr Obama’s retreat on this suggests that he is not yet convinced by the notion of driving through controversial legislation on Democratic votes alone, even if he could overcome the doubts of the Democrats’ own fiscal conservatives. Weighty calculations of principle, presentation and practical politics lean the other way.

The principle at stake is not only the promise Mr Obama made at his inauguration to transcend “petty grievances” and “worn-out dogmas”. Almost every president says something like that. A long-established idea in American politics also holds that big laws—the sort that alter the face of the country—are likelier to endure if they collect support from both parties. That was the thinking behind great bipartisan measures such as the creation of Social Security in 1935 and of Medicare in 1965, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and—in 1986—the tax reform engineered by Ronald Reagan and his ideological opposite, Speaker Tip O’Neill. Mr Obama says he wants to stop America from being bankrupted by health bills and the planet from frying. Those are causes big enough to make it worth travelling the extra mile to sign up the other party, which will one day return to government.

As for presentation, America has just buried Ted Kennedy, lionised now in a thousand editorials for having been, among other virtuous things, a shining exemplar of bipartisanship. Americans seemed to admire a senator whose firm stand on the left of the Democratic Party did not stop him from making Republican friends and cutting bargains with them in order to make laws—a talent that persuaded a veteran conservative pundit, George Will, to declare him the most consequential Kennedy brother. After a summer of ugly tribal arguments in town-hall meetings on health care, politicians may feel the need to pay lip service, at least, to the idea of bipartisanship.

And yet in the Washington think-tanks the passing of Ted Kennedy has revived a different debate. Is bipartisanship still feasible in today’s America? Is it even desirable? Pietro Nivola, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, has doubts on both counts. Grand bargains are harder in an age when both parties, but especially the Republicans, have become more ideological and cohesive. Congress no longer contains legions of conservative Democrats from the South or moderate Republicans from the north-east willing to make common cause—or laws. The gerrymandering of electoral districts has slashed the number of swing seats, forcing candidates to nurture their wild-eyed base, rather than reach out to moderates, to win their primaries. Religious polarisation has sharpened the gap between the parties, sucking believers into the Republican camp and driving the secular to the Democrats.

During the raucous fight over health care, Democrats have affected particular indignation over the remark in July of a Republican senator, Jim DeMint of South Carolina, that “if we’re able to stop Obama on this, it will be his Waterloo. It will break him.” How very non-bipartisan. And yet nothing could be more natural than for an opposition to scheme to thwart the governing party. Mr Nivola argues that rather than wringing their hands, Americans should welcome the fact that their parties have become aggressively opposed. “As in Europe,” he says, “the majority rules and the minority has to bide its time.” This produces clearer choices for voters and makes it easier to hold governments to account. Nothing wrong with that.

Unless, perhaps, you are the one who is going to be held to account. As anxious Democrats resume work next week, even his allies admit that Mr Obama has had a torrid summer. His approval rating has fallen from about 70% at the time of his inauguration to around 50%. Independents in particular seem to be losing faith. Health-care reform has taken a bashing. By mid-August only 46% of Americans approved of Mr Obama’s handling of it, down from 57% at the end of April. Americans understandably doubt whether any of the bills before Congress can cut costs and extend coverage at the same time. If health reform fails, energy legislation will falter too.

These are not circumstances in which Mr Obama will rush to heed the advice of those who want the Democrats to go it alone. White House aides say only that when the president returns to work he will be “very active”. He is scheduled to address a joint session of Congress on health care next Wednesday. As for the public option, it seems that he will still not insist on it if that puts off Republicans. Besides, if there is comfort for the president in the polls, it is last month’s finding by the Pew Research Centre that a growing proportion of Americans (29%) blame the Republican leadership rather than Mr Obama (17%) for their failure to work together. If nothing else, bipartisanship has always been an excellent way for presidents to spread the blame in case things go wrong.

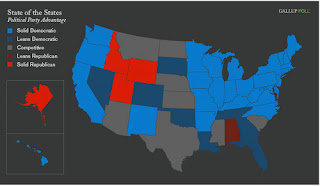

PRINCETON, NJ — An analysis of Gallup Poll Daily tracking data from the first six months of 2009 finds Massachusetts to be the most Democratic state in the nation, along with the District of Columbia. Utah and Wyoming are the most Republican states, as they were in 2008. Only four states show a sizeable Republican advantage in party identification, the same number as in 2008. That compares to 29 states plus the District of Columbia with sizeable Democratic advantages, also unchanged from last year.

These results are based on interviews with over 160,000 U.S. adults conducted between January and June 2009, including a minimum of 400 interviews for each state (305 in the District of Columbia). Each state’s data is weighted to demographic characteristics for that state to ensure it is representative of the state’s adult population.

Because the proportion of independents in each state varies considerably (from a low of 25% in Pennsylvania to a high of 50% in Rhode Island and New Hampshire), it is easiest to compare relative party strength using “leaned” party identification. Thus, the Democratic total represents the percentage of state residents who identify as Democratic, or who identify as independent but when asked a follow-up question say they lean to the Democratic Party. Likewise, the Republican total is the percentage of Republican identifiers and Republican-leaning independents in a state.

So, what does this all mean ?

Well, it’s not good news if you’re a Republican:

Since Obama was inaugurated, not much has changed in the political party landscape at the state level — the Democratic Party continues to hold a solid advantage in party identification in most states and in the nation as a whole. While the size of the Democratic advantage at the national level shrunk in recent months, this has been due to an increase in independent identification rather than an increase in Republican support. That finding is echoed here given that the total number of solid and leaning Republican states remains unchanged from last year. While the Republican Party is still able to compete in elections if they enjoy greater turnout from their supporters or greater support for its candidates from independent voters, the deck is clearly stacked in the Democratic Party’s favor for now.

Comments